The Great Myth Of Storytelling

In Business Communications

Once Upon a Time

The fervor around the wonders of storytelling in business communications has reached the point where we almost expect a carnival barker to appear touting, “Step into my tent and let me share how storytelling can make you rich and thin.”

There’s just one not-so-little detail that no one talks about.

When it comes to business communications, storytelling by its classic definition — a start, an end, and something going horribly awry in between — doesn’t work the vast majority of time. Companies don’t want to bring attention to their failures.

Who does?

Yet, there are ways to lift narratives without depending on the bad stuff. There are ways to shape pitches to journalists that align with how journalists write today.

That’s what we’re going to explore.

What Exactly Do We

Mean by Business

Storytelling?

The word “storytelling” in business can be confusing. It brings to mind fiction that follows the arc we mentioned in the introduction — a beginning, climax, resolution, and bad stuff (there’s that phrase again) happening in between. Inserting negativity into narratives isn’t exactly a natural act for companies.

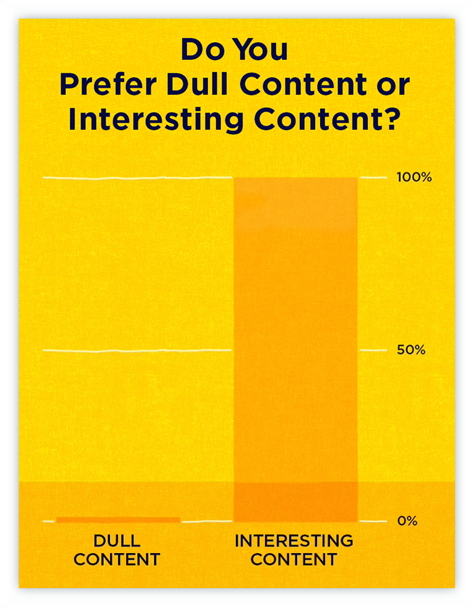

What you can do is borrow techniques from traditional storytelling to help frame what you want to convey as interestingly as possible. There is a clear business case for doing this. Given a choice between boring and interesting, human beings will choose interesting 100% of the time.

In a business context, storytelling means thinking more like a journalist than like a novelist. It means building something human and interesting around a core premise. It’s finding a way to bring to life something that might otherwise seem mundane.

Feature stories in business publications depend on these techniques. It’s not enough to share a success story or a lesson learned. The narrative comes packaged with the unexpected and the type of details that tell you this really happened.

Communicators should be doing the same.

Digging Out the Story

Storytelling gold rarely arrives on a platinum platter.

You have to find it.

The beauty of the discovery process is that you might start on point A, which takes you to point B, which lands you unexpectedly on point C where the gold is buried. Compelling fodder for communications can reside in unlikely places.

Some time ago, National Semiconductor asked us to develop a campaign for a semiconductor called an EEPROM (electrically erasable programmable read-only memory), a technical product not exactly a natural for mainstream media attention.

We asked the product manager about potential uses for the new chip. It turned out one of the target applications was keyless locks for cars. Apparently, criminals were intercepting the signal from keyless locks in order to break into cars. The EEPROM had a rolling code generator that prevented the criminals from intercepting the signal and opening the car door.

Next, a brainstorm pointed us to the insurance industry and an in-depth examination of auto theft. We even discovered that an early theft-prevention device was a blow-up man designed to sit in the driver’s seat and act as a deterrent to thieves.

Based on the research, we were able to package a story for the EEPROM that played on local newscasts. The key was offering a hook that mass consumers could relate to — car break-ins, and how they impact the cost of car insurance. The broadcasts presented the EEPROM as a solution to stop car thefts, circumventing the need for heavy technical explanations.

By the same token, a photo ionization detector breaking down chemicals under an ultraviolet light doesn’t exactly send the heart racing. But take that same monitor and catch “paddle dopers” (table tennis players who add chemicals to their paddles for greater spin), and suddenly a gas detection company is in the media.

Discovering an anecdote, a contrarian fact or just a strange happenstance is often enough to lift a narrative. Even companies that seem impossibly dull have something interesting to share. But these stories typically lie below the surface. Finding them requires digging — sometimes, a lot of digging. Research and persistence are essential with your questions serving as a way to excavate story shards.

Whether you’re in-house or on the agency side, you need to be prepared to ask probing questions of your sources. Framing is important. At the same time, you want to make your source feel comfortable enough to open up and talk about things that they themselves had not previously considered. Here are some approaches to bear in mind:

- Do your homework. This means not only understanding the topic, but also the person you’re interviewing. It can be as easy as looking through their LinkedIn profile, for context.

- Start the interview before the interview. Email a few questions in advance to set things in motion. Explain that you are looking for drama, not a calculus tutorial.

- Warm up. Most people don’t automatically open up to someone they don’t know, even if they are on the same team. Start with a few easy questions to get the person talking. In this way you build momentum leading into the tougher questions.

- Talk one-on-one. A topic usually involves multiple people. Avoid interviewing them together. You will get more useful information from a one-on-one interview than in a group setting. You can then use that information to help form questions for subsequent interviews.

- Ask open-ended questions. You want to encourage the person to talk. You are looking to elicit mini-narratives, not “yes” and “no”. The best storytelling material carries an emotional dimension. Questions like “What were you feeling when … ?” provide a safe ground for the source to open up. But you also need to probe the challenges, the things that didn’t go according to plan.

- Improvise. Listen to what’s being said. You need to have questions prepared, but be willing to explore unexpected areas that come up too. If an engineer casually mentions he was hired to figure out if a piece of technology could be salvaged, go deeper to understand what derailed the technology before the engineer arrived on the scene.

Boring, predictable questioning will inevitably lead to boring, predictable answers. Your questions should poke and cajole (without hurting the subject matter expert).

Three Go-to Storytelling Techniques

Think of storytelling as a way to shape a narrative to better resonate with the audience.

The following storytelling techniques do exactly that.

Conversational language. How much time would you want to spend with a person who spoke like a press release? “Today, I am pleased to announce that I consumed a double cappuccino designed by a skilled barista who executed the espresso extraction at 202°F.” Not exactly a killer ice breaker.

There’s something about the business environment that can change the character of even the most chill individual to the extent where the language they use to address the outside world suddenly becomes stiff as mahogany.

Business has a way of squeezing the life out of a piece of writing too.

Even in business — perhaps especially in business — people are likely to be much more receptive to a communication if it sounds as if it’s coming from an actual human being. That doesn’t mean that you suddenly start using slang and peppering your writing with “dude.”

For B2B companies that often fall into the trap of corporate speak, the use of conversational language alone can differentiate.

Contrast. As we’ve established, most businesses are not keen to focus on their shortcomings. Yet the failure story is at its core one of contrast: the gap between the old and the new way of doing things. The greater the difference between the old and new way, the more interesting the story.

When it comes to corporate stories, the past might not be entirely flattering, but without it, the journalist or reader has no way to frame the situation. In a media interview shortly before its IPO, Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky went into detail about the company’s efforts to navigate COVID-19, which nearly killed the business. The resulting story is something of a rollercoaster from which Airbnb emerges as victorious in the end.

Was sharing negative points to create this contrast risky? We would argue no. Because Chesky and Airbnb’s PR team already knew the story has a happy ending.

Humanity: Developing your characters — the people involved in a given story — brings humanity to the fore. It can mean the difference between something getting traction and falling by the wayside.

Yet most executives — and the people who communicate on their behalf — make a conscious effort to hide their humanity. We’re told early on that business is business, personal is personal, and the two shouldn’t overlap.

It’s a missed opportunity.

What it means in practice is being willing to show the personality behind the corporation or whatever entity it may be. Personal perspectives are central to achieving this; drawing attention to quirks can also go a long way as it helps provide the color that people crave.

For an executive in the tech sector, it could be as simple as sharing an experience of buying digital products for their family. That’s exactly what the then CEO of Cypress Hassane El-Khoury did during an interview with Barron’s recounting his experience at Best Buy during Black Friday to purchase four Amazon Echos.

By the way, your “characters” can be anyone in the company, not just the CEO.

The Quest for Interesting

Consider that you to go to an event and meet someone new. Let’s call this person Donald (Freudian at work?). Donald goes on and on … and on talking about himself. What happens?

Exactly. We find a way to get away from Donald whom we’ve sized up as a total bore.

Why should it be any different for companies that only talk about themselves without showing interest in what’s happening in the wider world. An outward perspective offers the path for finding interesting material.

Earlier we discussed contrast, humanity and conversational language as ways to lift a narrative. Here are a few more storytelling techniques:

Failure with a little “f”. Journalists and readers love failure. Companies can find the middle ground with small “f” failure stories that don’t constitute major upheaval.

A story about McDonald’s Innovation Center discussed a contraption that dispensed the right number of Chicken McNuggets for cooking so employees wouldn’t have to count them out each time. The invention never saw the light of the day.

UPS landed a story in The Wall Street Journal by calling out that 30% of new drivers flunked their training before the company retooled its curriculum.

The point is that even a small failure creates tension that makes a story compelling. And, again, where’s the risk? You already know the story ends on a positive note.

Anecdotes open doors. Anecdotal content in business publications ranges from 15% to 25% per feature story. There is good reason for this: they humanize a story, add levity and entertainment value. If someone audited the content created by the communications function around the world, we suspect less than 3% would be anecdotal. That’s a massive miss. We will look at the power of anecdotes in more detail in a minute, but suffice to say, they can make the most vanilla content suddenly breathe.

Take a position. Executives often believe that the middle ground is the safe ground. Yet, the reality is by doing so, they’re actually not taking a position at all.

True thought leadership delivers a fresh point of view, often running counter to the conventional way of thinking. It pushes discourse into unexpected terrain. It causes the audience to dig deeper into the idea or even react with defensiveness. It gets noticed. Consider Nike’s storytelling around mixed-race athletes in Japan. By highlighting racism in society, the brand ruffled feathers, but also sparked an important discussion and achieved widespread publicity that was ultimately good for business. There’s a reason it’s called “thought leadership,” not “thought followship.”

The Power of the Humble Anecdote

We noted earlier that anecdotes account for a significant portion of journalistic stories. A few years ago, we analyzed three months’ worth of tech stories in The Economist, breaking down the content type by category.

It turned out that 17% of the articles were anecdotal. Yet anecdotes barely show up in the content developed by communicators.

There’s the mistaken belief that anecdotes are inconsequential or even fluff. It also is the result of misplaced efficiency: if your task is to communicate a corporate message, your default thinking is that you should exclude information that diverts attention from that message.

In media training, executives are lectured repeatedly to stay “on message.” But pristine messages fail to land because they sound as if they are generated by a machine rather than a human being. Journalists see through them instantly.

People are naturally resistant to “messaging,” but receptive to anecdotal snapshots. Suddenly there is something they are able to relate to. Anecdotes offer a way to pull the reader into the story.

Consider examples from the media. A story in The New York Times talks about how IBM coders used to spend their breaks having snowball fights in Central Park. Think about the image of legendary corporate leaders. Steve Jobs is known as much for having lived in a virtually unfurnished house due to his exacting design principles as he is for creating one of the world’s most valuable companies. Marc Benioff is known as a student of Zen as much as he is a technology CEO. It is largely down to anecdotes that we see people and organizations the way we do.

In crunching its mammoth databases, Walmart saw that before major storms struck there was a run on flashlights and batteries, as to be expected. But there was also a spike in demand for Pop-Tarts, prompting the retailer to stock up on the sugary breakfast snack in threatened geographies during bad weather seasons. The anecdote added a fresh dimension to a technical story on data analytics.

No one ever says, “Wow, what a great message.” Yet the anecdote can move people to proclaim, “What a great story.”

The David vs. Goliath Frame for Corporate Stories

Stories with David and Goliath DNA have an enduring quality that people respond to — the unexpected. No one expects a David to beat the proverbial Goliath. Still, we root for him.

The story of retail investors coming together on Reddit to buy up GameStop shares was thrilling mainly because it pitted the everyman against the titans of Wall Street.

The same technique can be compelling for brands in the business world. Think about the ways in which the subject of your communications is standing against something big. Often, it is not a case of pitting one brand against another, but of a company taking on established institutions.

Part of the reason Tesla has gained as much traction as it has is its continued framing as a hardworking underdog with an environmental mission taking on the vested interests of the automotive establishment. Whether you believe the hype or not, it’s easy to see why so many people have bought into the story. Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have a CEO who guest hosts Saturday Night Live.

If you play your hand well enough, over time you inevitably cease to be David and become the Goliath.

Malcolm Gladwell, who wrote a book on the subject of David and Goliath situations, has noted that Davids actually win almost a third of the time. “Effort can trump ability,” he wrote in The New Yorker, “because relentless effort is in fact something rarer than the ability to engage in some finely tuned act of motor coordination.”

This notion appeals deeply to the human psyche. But the “how” is crucial as the vehicle to tell the story of succeeding when the circumstances suggest it shouldn’t play out this way. The same principle can be applied to telling a company’s story.

Companies, especially in the technology sector, leapfrog the status quo every day. Unfortunately, the typical company wants to jump right to the punchline instead of capturing the “how” and all the drama that goes with it.

Those anecdotes, numbers, obstacles, perspectives, emotions, derailments and so forth bring out an entertainment value that elevates the accomplishment.

We have a natural affinity for underdogs. The fact that your subject is not the leader in its field can work to your advantage. Indeed, people and companies often show their best characteristics in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges or unbeatable competition.

And it makes for good “TV.”

Supply and Demand in the Media Relations “Market”

The relationship between journalists and PR is never going to be a perfect fit.

Each party has a different agenda. Journalists strive for objectivity in helping their readers make sense of an industry, a company or a topic. Companies want to be cast in a light that resonates with their target audiences, particularly those in a position to buy their products or services.

Applying economic theory to the relationship between PR and journalism helps to bridge this gap.

Journalists need material to produce industry features or news stories not already in the public domain. The internet has largely commoditized the news release, especially in the B2B world when it comes to product announcements. We asked a number of journalists a simple question: “What word or words do you associate with the news release?”

What started as primary research morphed into a therapy session. The tamer answers included “formulaic”; “obfuscation”; “trashcan”; “old school” and “long and boring.” It seems safe to conclude that journalists don’t value the news release. Yet, each year in the U.S. alone companies distribute roughly 750,000 news releases.

To put this into context, we figure on 30 hours going into the creation of a typical news release with time valued at around $200 per hour. This means that companies are spending $4,500,000,000 on content for which there’s very little demand. It makes no sense.

It’s also the reason that the relationship between PR and journalists can be contentious at times. Companies, frustrated by the lack of ROI from announcements, send PR to pummel journalists into submission to write about announcements they don’t care about.

To better align with journalistic demand, we need to put more energy into creating content that addresses industry issues and information not in the public domain. This is what journalists value.

We need to think like a journalist, not only identifying the core newsworthy element, but pulling together a mix of commentary, anecdotes, facts, research and numbers that allow for a fresh narrative. And it requires digging as discussed earlier. The journalist is still free to interpret it all as they choose, but the raw material has to be relevant. We’ve come to call this one-off storytelling.

When supply perfectly meets demand in the economics world, they call it equilibrium. It’s not realistic to think we’re going to find this in the relationship between PR and journalists. But a large part of the friction would go away if PR shifted to an emphasis on industry issues and information not in the public domain.

Words are Only Part of the Picture

Your choice of words makes a big difference to the way a piece of information travels. Visual imagery can be equally important for all forms of “communications,” corporate blogs, content marketing and presentations as well as traditional PR activities.

Just as you do not have to be a great novelist to tell a good story, you do not have to be another Banksy to use images to good effect. A “word visual” is easy to produce — it just requires a bit of imagination. As the name suggests, words form the basis of it. There are four main types:

Clever words that stand on their own: Here, the words (sometimes handwritten), carry the day. Little or no design goes into this type of visual storytelling. It could be as simple as an image of a note scribbled on a piece of notepaper. It could be a hand-drawn chart or diagram with a caption. A few choice words, strikingly presented, can add levity and interest.

Celebrity and speech cloud: This technique can go a long way in the B2B space, where you don’t expect a pop culture figure to surface. Of course, your subject doesn’t have to be famous, or even human. The point is that the effect can be amusing.

Old visual, new words: Take something that exists — a book, movie poster, billboard, someone holding up a placard, even a soft-drink can — and replace the words with your own. You should not be afraid to borrow from the world of consumer goods and branding. The effect can stop the reader with a “what the heck.”

Words that carry a simple image: Here, the image makes perfect contextual sense. The Economist’s captions are masterful in this regard. The book “Whatever You Think, Think The Opposite” by the UK adman Paul Arden also offers brilliant examples of this in action. Or you could devise a GIF where the words drive the action.

IBM has tried to get its staff thinking more in terms of design, guided by this understanding: “Design is everyone’s job. Not everyone is a designer, but everybody has to have the user as their North Star.”

The same logic applies to communicators. The recipient of your communications should be your North Star. That means understanding what will provoke a reaction from them and make them receptive to the message you want to convey.

One final piece of guidance: It sounds simplistic, but as you come across imagery that you like, capture it. Put it somewhere where you can see it or easily refer to it.

Just because you don’t have a background in the visual arts, don’t feel that this world is off-limits to you. With a bit of creative thinking, you can use images to frame or augment whatever it is you want to say.

A Word on Courage

After conducting our storytelling workshop over the years, a theme has emerged.

By the close of the workshop, people buy into the concepts. They jump back into their jobs with renewed determination to communicate with conversational language and a “show-don’t-tell” attitude, only to run into a force called stakeholder approval.

We continually hear back from participants that they try to write with the techniques of storytelling — they really do — but by the time their content goes through the corporate meat grinder, it looks nothing like the original form.

There’s no easy answer for this challenge. Business executives often perceive safety in sameness. Anything that makes a company stand out can be frightening. A lot of senior marketers and communicators have also been grounded in “me marketing.” They believe corporate narratives should espouse only the virtues of the company. Some believe audiences compartmentalize, so let’s leave the entertaining to people like Steven Spielberg. Others are simply risk averse. Even a touch of emotion in business communications can make them uneasy.

Whether you work at an agency or in-house, you need courage to move things forward. You must not feel defeated by the obstacles that are sure to come your way. Telling good stories is something worth fighting for. Instead of arguing every point, pick the areas where you have the greatest strength of conviction.

The same approach applies to creativity more widely. Part of the problem is that practitioners are often focused on “pleasing” clients or internal stakeholders rather than on doing what they believe in their hearts to be the right thing. To become true consultants, we need to move out of the “pleasing” space and into one where we make a persuasive case for deviating from the status quo.

When you come up against resistance, use your interactions as an opportunity to educate your stakeholders. Share the context that shapes your thinking. Even stakeholders from the old school recognize that communicating the same points the same way as your competitors is wrong. Let them read for themselves, again with context, how you’re striving for a differentiated voice.

More than logic, emotion must also be part of these discussions. Allow your passion to come to the fore.

Your point of view might not win the day the first time.

Or the second time.

But eventually, your strength of conviction will win over others.

The Story is Always There

The headline above sounds so much better than saying “Interesting stuff is always there.”

Yet, that’s really what we mean.

Storytelling techniques make your communications more interesting. And as you saw earlier in our decidedly unscientific study, given a choice between dull and interesting, people will gravitate to the interesting every time.

We appreciate your interest in the topic.

If you have any questions or comments, we’d love to hear from you.

Additional Resources

You might find the following useful:

- Interactive Microsite on Storytelling Techniques

- PR Week: “People Have Misunderstood the Meaning of Storytelling”

- SlideShare: “The Story is Always There”

- Blog: “Five Storytelling Techniques to Give Business Communications Liftoff”

- Mumbrella:“Improve Your Storytelling Abilities or Become Marginalised”

About The Hoffman Agency

We’re a global communications consultancy that solves problems — the tougher the better — for tech companies.

While our heritage lies in earned media and PR, we are increasingly executing “blended” campaigns that include owned media and paid media.

To scale storytelling techniques across a company, we have also developed a workshop curriculum that can be tailored by audiences ranging from in-house communications to product managers to engineers/scientists.

For more information: